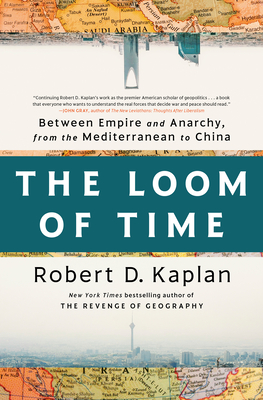

One of the women in my book club mentioned this book and as I thought I should be better informed about the Middle East, I decided to read it.

Here’s the blurb …

A stunning exploration of the Greater Middle East, where lasting stability has often seemed just out of reach but may hold the key to the shifting world order of the twenty-first century

The Greater Middle East, which Robert D. Kaplan defines as the vast region between the Mediterranean and China, encompassing much of the Arab world, parts of northern Africa, and Asia, existed for millennia as the crossroads of empire: Macedonian, Roman, Persian, Mongol, Ottoman, British, Soviet, American. But with the dissolution of empires in the twentieth century, postcolonial states have endeavored to maintain stability in the face of power struggles between factions, leadership vacuums, and the arbitrary borders drawn by exiting imperial rulers with little regard for geography or political groups on the ground. In the Loom of Time, Kaplan explores this broad, fraught space through reporting and travel writing to reveal deeper truths about the impacts of history on the present and how the requirements of stability over anarchy are often in conflict with the ideals of democratic governance.

In The Loom of Time, Kaplan makes the case for realism as an approach to the Greater Middle East. Just as Western attempts at democracy promotion across the Middle East have failed, a new form of economic imperialism is emerging today as China’s ambitions fall squarely within the region as the key link between Europe and East Asia. As in the past, the Greater Middle East will be a register of future great power struggles across the globe. And like in the past, thousands of years of imperial rule will continue to cast a long shadow on politics as it is practiced today.

To piece together the history of this remarkable place and what it suggests for the future, Kaplan weaves together classic texts, immersive travel writing, and a great variety of voices from every country that all compel the reader to look closely at the realities on the ground and to prioritize these facts over ideals on paper. The Loom of Time is a challenging, clear-eyed book that promises to reframe our vision of the global twenty-first century.

It is clear that Kaplan has spent a lot of time travelling in the Middle East (over a number of years), thinking about it and researching it. Although it was recently published, it was before Trump’s second presidency, which I think will have a profound impact on world politics.

I thought about anarchy and autocracy and how the latter might be preferred. There is information about the history – country by country – the revolutions, the ethnic groups, and the religions.

A review